By SBLAKE

23 June 2010

Leaf through the pages of almost any life sciences journal, and you will come across advertisements for HeLa cells, living laboratory tools that have formed the basis of an incalculably vast amount of biomedical research since the early 1950s. Retailing at anything from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars for a small vial, different versions of this indispensable elixir are hawked by laboratory supply companies the world over. Many of these products’ consumers have long been aware that there is a human story behind HeLa’s blandly commercialised ubiquity; now Rebecca Skloot’s remarkable book has appeared to fill in all the details. The moniker ‘HeLa’ is derived from the name of a young African-American mother of five, whose agonising death in a Jim Crow era charity hospital gave rise to a quiet revolution in medicine. In January 1951, at the age of 30, Henrietta Lacks was admitted to the ‘Coloured Only’ examination room of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, complaining of abdominal pain and irregular bleeding. A week later she was back to receive radium treatment for cervical cancer. Before operating, the surgeon shaved a small sample of tissue from the tumour on her cervix and sent it off to the laboratory of George and Margaret Gey (pronounced ‘Guy’), two research scientists who were engaged in a frustrating quest to keep human cells alive outside the body.

For years the Geys had been taking tissue samples from Johns Hopkins patients, nurturing the cells with warmth, nutrition and gentle movement, trying to coax them into continuing to divide. This had worked with mouse cells a few years earlier, but human cells were proving fussier. The Geys experimented with recipe after recipe for cell chow – the ‘nutritional medium’ – but their efforts resulted in, at best, a few days of survival. By 1951 a certain fatalism had settled over the lab’s day-to-day proceedings, and so when Henrietta Lacks’s sample appeared, the technician, Mary Kubicek, finished her lunch before embarking on the lonely little performance she had gone through so many times before. After sterilising everything and donning a surgical cap and mask, she cut the sample into one-millimetre dice, dropped each tiny square onto a chicken blood clot in a test tube, and covered it with a few drops of the mixture of broths, salts and umbilical cord blood that was the cells’ experimental plat du jour. She then plugged each test tube with a rubber stopper, labelled it ‘HeLa’ for the patient’s first and last names, and inserted it into a crazy rig that George Gey had fashioned out of junkyard scraps to keep the cells warm and in constant motion.

Con't..

http://sblake.livejournal.com/325375.html

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.

.

May love and laughter light your days,

and warm your heart and home.

May good and faithful friends be yours,

wherever you may roam.

May peace and plenty bless your world

with joy that long endures.

May all life's passing seasons

bring the best to you and yours !

*******

Thanks Pbtrue1. :)

May love and laughter light your days,

and warm your heart and home.

May good and faithful friends be yours,

wherever you may roam.

May peace and plenty bless your world

with joy that long endures.

May all life's passing seasons

bring the best to you and yours !

*******

Thanks Pbtrue1. :)

.

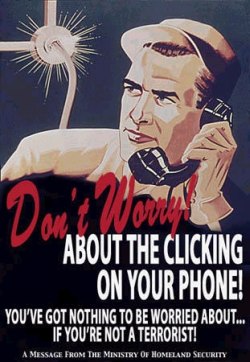

"Hello to our friends and fans in domestic surveillance."

.

"Hello to our friends and fans in domestic surveillance."

*Hee Hee*

Submitted by Alice on Sun, 08/05/2007 - 4:02am.

MM.. :)

*Hee Hee*

Submitted by Alice on Sun, 08/05/2007 - 4:02am.

MM.. :)

I'm Eighteen (Album Version)

I'm Eighteen (Album Version)

No comments:

Post a Comment